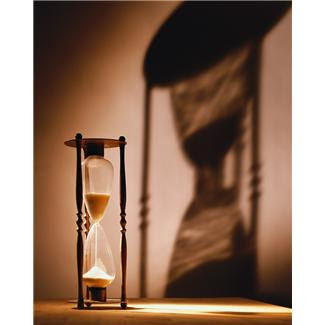

Newswise, October 26, 2016 — As men age, they continue to

follow dominant ideas of masculinity learned as youth, leaving them unequipped

for the assaults of old age, according to a new study.

The mismatch between aging and the often ageless expectations

of popular masculinity leaves senior men without a blueprint to behave or

handle emotions, according to a new literature review from Case Western Reserve

University.

Men who embodied prevailing cultural and societal hallmarks of

manliness as younger men—projecting an aura of toughness and independence,

avoiding crying and vulnerability, while courageously taking risks—are

confronted by the development of health problems, loss of spouses and loved

ones, retirement and needing to be a caregiver for ailing family members in

later life.

“Who you are in the past is embedded in you,” said Kaitlyn

Barnes Langendoerfer, a doctoral student in sociology at Case Western Reserve

and co-author of the review, which mined narrative data from nearly 100

previously published studies.

“Men have trouble

dealing with older age because they’ve followed a masculinity script that left

little room for them to negotiate unavoidable problems.”

“In our study, we hear men struggling with grief—which is a

vulnerable state—and caregiving, which is associated with femininity,” she

said.

“If they must cry, men feel it’s to be done in the home, away

from others, even when spouse has died. They have to renegotiate their

masculinity in order to deal with what life is bringing their way.”

This masculinity “script” still embraced by older men was

outlined as the four-part Blueprint of Manhood, first published by

sociologist Robert Brannon when the men in the studies were entering adulthood

in the 1970’s. The blueprint included:

No Sissy Stuff - men are to avoid

being feminine, show no weaknesses and hide intimate aspects of their lives.

The Big Wheel - men must gain and

retain respect and power and are expected to seek success in all they do.

The Sturdy Oak – men are to be

‘‘the strong, silent type” by projecting an air of confidence and remaining

calm no matter what.

Give ‘em Hell – men are to be

tough, adventurous, never give up and live life on the edge.

“We’re all aging; it’s a fact of life. But as men age, they’re

unable to be who they were, and that creates a dissonance that is hard to

reconcile,” said Langendoerfer, who studies aging in men.

“We need to better understand how older men adapt to their

stressors—high suicide rates, emotions they stifle, avoiding the doctor—to

hopefully help them build better lives in older age,” she said.

The review, published in the journal Men and

Masculinities, was co-written by Edward Thompson Jr., an emeritus professor

of sociology and anthropology at the College of the Holy Cross and now an

affiliate of the Department of Sociology at Case Western Reserve.

Most of the data came from studies with white, middle-class

men from the United States, Canada and Europe who had stable careers. “More

research inclusive of different races and socioeconomic backgrounds is needed

to obtain a more complete picture of how older men adapt,” Langendoerfer said.