UCLA-led study shows 5 percent of population ages

faster, faces shorter lifespan

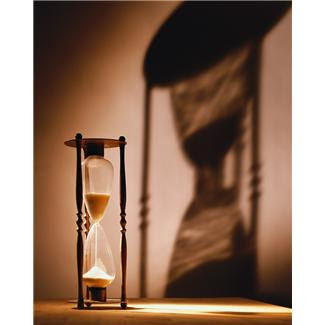

The rate of your biological clock influences how long you'll

live.

Why do some people lead a perfectly healthy lifestyle yet

still die young? A new international study suggests that the answer lies in our

DNA.

Newswise, October 3, 2016 — UCLA geneticist Steve Horvath led a team of 65 scientists in seven

countries to record age-related changes to human DNA, calculate biological age

and estimate a person’s lifespan. A higher biological age—regardless of

chronological age—consistently predicted an earlier death.

The findings are published in today’s edition of the journal Aging.

“Our research reveals valuable clues into what causes human

aging, marking a first step toward developing targeted methods to slow the

process,” said principal investigator Horvath, a professor of human genetics

and biostatistics at UCLA’s David Geffen School of Medicine and Fielding School of Public Health.

Drawing on 13 sets of data, including the landmark Framingham

Heart Study and Women’s Health Initiative, a consortium of 25 institutions

analyzed the DNA in blood samples collected from more than 13,000 people in the

United States and Europe.

Applying a variety of molecular methods, including an epigenetic clock developed by Horvath in 2013, the

scientists measured the aging rates of each individual.

The clock calculates the aging of blood and other tissues by

tracking methylation, a natural process that chemically alters DNA over time.

By comparing chronological age to the blood’s biological age, the scientists

used the clock to predict each person’s life expectancy.

“We were stunned to see that the epigenetic clock was able to

predict the lifespans of Caucasians, Hispanics and African-Americans,” said

first author Brian Chen, a postdoctoral fellow at the National Institute

on Aging.

“This rang true even after adjusting for traditional risk

factors like age, gender, smoking, body-mass index, disease history and blood

cell counts.”

The group’s findings, however, don’t bode well for everyone.

“We discovered that 5 percent of the population ages at a

faster biological rate, resulting in a shorter life expectancy,” Horvath said.

“Accelerated aging increases these adults’ risk of death by 50 percent at any

age.”

For example, two 60-year-old men, Peter and Joe, both smoke to

deal with high stress. Peter’s epigenetic aging rate ranks in the top 5

percent, while Joe’s aging rate is average. The likelihood of Peter dying

within the next 10 years is 75 percent compared to 60 percent for Joe.

The preliminary finding may explain why some individuals die

young – even when they follow a nutritious diet, exercise regularly, drink in

moderation and don’t smoke.

“While a healthful lifestyle may help extend life expectancy, our innate aging process prevents us from cheating death forever,” Horvath emphasized. “Yet risk factors like smoking, diabetes and high blood pressure still predict mortality more strongly than one’s epigenetic aging rate.”

Scientists have long searched to identify biomarkers for

biological age, according to coauthor Dr. Douglas Kiel, a professor at Harvard Medical School and

a senior scientist for the Institute of Aging Research at Hebrew SeniorLife.

“In geriatric medicine, we are always struck by the difference

between our patients’ chronological age and how old they appear

physiologically,” said Kiel.

“This study validates the use of DNA methylation as a

biomarker for biological age. And if we can prove that DNA methylation

accelerates aging, we can devise strategies to slow the rate and maximize a

person’s years of good health.”

The precise role of epigenetic changes in aging and death,

however, remains unknown, said coauthor Dr.

Themistocles Assimes, an assistant professor of cardiovascular medicine at

Stanford University School of Medicine.

“Do the epigenetic changes associated with chronological aging

directly cause death in older people?” said Assimes.

“Perhaps they merely enhance the development of certain

diseases--or cripple one’s ability to resist the progression of disease after

it has taken root. Future research is needed to address these questions.”

Larger studies focused only on cases with well-documented

causes of death will help scientists tease out the relationship between

epigenetic age and specific diseases, he added.

By 2017, according to the World Health Organization, the number of people worldwide

over age 65 will outnumber those under age 5 for the first time in recorded

history.

By 2050, the proportion of the global population over 60 will

double from 11 to 22 percent. Many countries will be ill-prepared to keep pace

with the high costs associated with disease and disability as more people live

longer, said Horvath.

“We must find interventions that prolong healthy living by

five to 20 years. We don’t have time, however, to follow a person for decades

to test whether a new drug works.” said Horvath. “The epigenetic clock would

allow scientists to quickly evaluate the effect of anti-aging therapies in only

three years.”

The University of California has applied for a provisional

patent on the epigenetic clock.

No comments:

Post a Comment